Pope's passing reminds me of some personal stories of terminal lucidity

I woke up on the morning of Monday, April 21, 2025. As per usual, like many people, the first thing I did was reach for my phone.

Usually, I check social media first to see if I missed anything in the six hours I was sleeping. Maybe I will check some sports scores. I have made it a habit to avoid looking at news sites. It depresses me.

For some reason, on this morning, I opened some news app first. In big bold letters which took up most of the screen was written, "Pope Francis dies."

What??? Didn't I just see him yesterday make an appearance at the Vatican on the balcony of his residence. Didn't I hear him speak a few words to address the throng of people who had assembled in St. Peter's Square to celebrate Easter? Didn't he even ride through the crowd afterwards in the famed Popemobile. How could he be dead?

It was silly to ask that. Tomorrow is not guaranteed to any of us – not even to the seemingly healthiest, strongest, and youngest among us... nor the holiest.

Pope Francis wasn't young, healthy, and strong. He was 88 years old. He had just spent 38 days in the hospital. He was only recently discharged – on March 23 – after coming close to death as a result of double pneumonia. He was on strict orders to rest.

But how could he rest? Easter was right around the corner. And he was the Pope.

Somehow, Francis, in his weakened state and having had barely evaded death only weeks before, mustered the strength to fulfill his duties as the head of the Catholic Church and give a benediction to the 50,000 people gathered in St. Peter's Square, as well as all people, not only Catholics, world-wide.

He had even taken the time, earlier in the day, to meet with U.S. Vice President, J.D. Vance, and his wife. Sadly, it would be Pope Francis' final diplomatic meeting of his life.

The following morning he was dead. He started feeling ill around 5:30 a.m., according to the Vatican, and fell into a coma and just a couple of hours later, at 7:35 a.m. Vatican time, the Pope was pronounced dead.

The Pope's, surprising, rally and flurry of activities in the hours preceding his death got me thinking about the concept of "moments of lucidity." After some brief research, I found out the term I may really be looking for is "terminal lucidity."

The Cleveland Clinic defines terminal lucidity as:

Terminal lucidity, or “the surge,” is an unexpected episode (occurrence) of clarity and energy before death. Neurodegenerative conditions that lead to dementia, like Alzheimer’s disease, cause irreversible mental decline that can be hard to watch in a loved one. But terminal lucidity is a surprising exception where a person rallies. They may seem more like themselves again — briefly — before declining again. As the name suggests, terminal lucidity is usually a sign that death is near.

Terminal lucidity isn’t an official diagnosis. And not everyone who’s nearing death experiences it. Most healthcare providers who work with people who are dying only witness a few dozen incidents over their careers. But when these episodes do happen, they’re memorable for all who witness them.

Watching a dying loved one regain their ability and enthusiasm to engage can spark a flood of confusing emotions — from heartbreak to joy. It’s important to work through these feelings as you support your loved one through their final days, while caring for yourself, too.

The term may not, exactly, apply to what we witnessed with the Pope. The Pope didn't suffer from dementia, as far as we know. He seemed very sharp, mentally, right up to the very end, even thanking his nurse for allowing him to parade through the Square. According to the Vatican, the Pope even gave his nurse, Massimiliano Strappetti, a final "goodbye" gesture just minutes before slipping into his coma.

However, there is no doubt that Pope Francis knew, for lack of a better term, that his days were numbered. Perhaps, in his mind, he made it a goal of his to make it to Easter. He summoned all the physical, mental, and spiritual strength he had in the days and weeks after his discharge on March 23 to prepare to make – more than likely – a final appearance before the people he loved and to which he dedicated his life of servitude.

We've seen it before. Just recently, former U.S. President, Jimmy Carter, despite being in hospice and approaching 100 years old, expressed a desire and a goal to live long enough to cast a vote for presidential candidate, Kamala Harris.

There have been other stories of terminal patients hanging on long enough to see a son or daughter get married, or surviving just long enough to be able to hold a newborn grandchild in their hand just one time.

In the mid 1990's, I used to go to the casino two or three times per month. This would have been around the time Foxwoods in Connecticut first opened up. Sometimes I would take the hour long drive myself to the casino, but, most of the time, I would go with my best buddy, Charlie, and two of my cousins, Jorge and Carlos.

My cousins were both muscular and very good looking. I am, totally, comfortable saying that. They also have three sisters that are drop dead gorgeous. It's almost unfair how much they hogged the "attractive" genes in our family.

Jorge and Carlos were wild. They were free spirits.

Usually, I'd be the one to drive us to the casino. Jorge and Carlos only owned motorcycles, of course.

I would have the T-Tops off on my Firebird, and I'd be doing 75 down the highway. The CD player would be cranking Van Halen. We'd be singing at the top of our lungs, "Panama! Panama!" (that doesn't mean we were big fans of the country – "Panama" was one of Van Halen's biggest hits).

Panama by Van Halen

By my standards, I thought I was driving pretty fast, maybe even borderline reckless. Not by Carlos and Jorge's standards, who would always sit in the back seat.

Inevitably, at some point, Carlos would lean forward from the back seat, pop his head in between the two front seats. and rest his chin on my right shoulder, and use one of those voices a child uses when they want something, "Hey, Tony, this thing go any faster? Come on, man, I know it can. I wanna get there! Let's go!"

Sadly, Carlos got diagnosed with brain cancer around the age of 40. Around that same time he had just bought a fixer-upper – a cheap house with a lot of potential that needed a lot of repairs. Carlos, not surprisingly, was a very good handyman and skilled carpenter. He was good with his hands.

He spoke, excitedly, about all the things he wanted to do to the house. The thing he was most excited about was his bathroom, especially the walk in shower he wanted to put in.

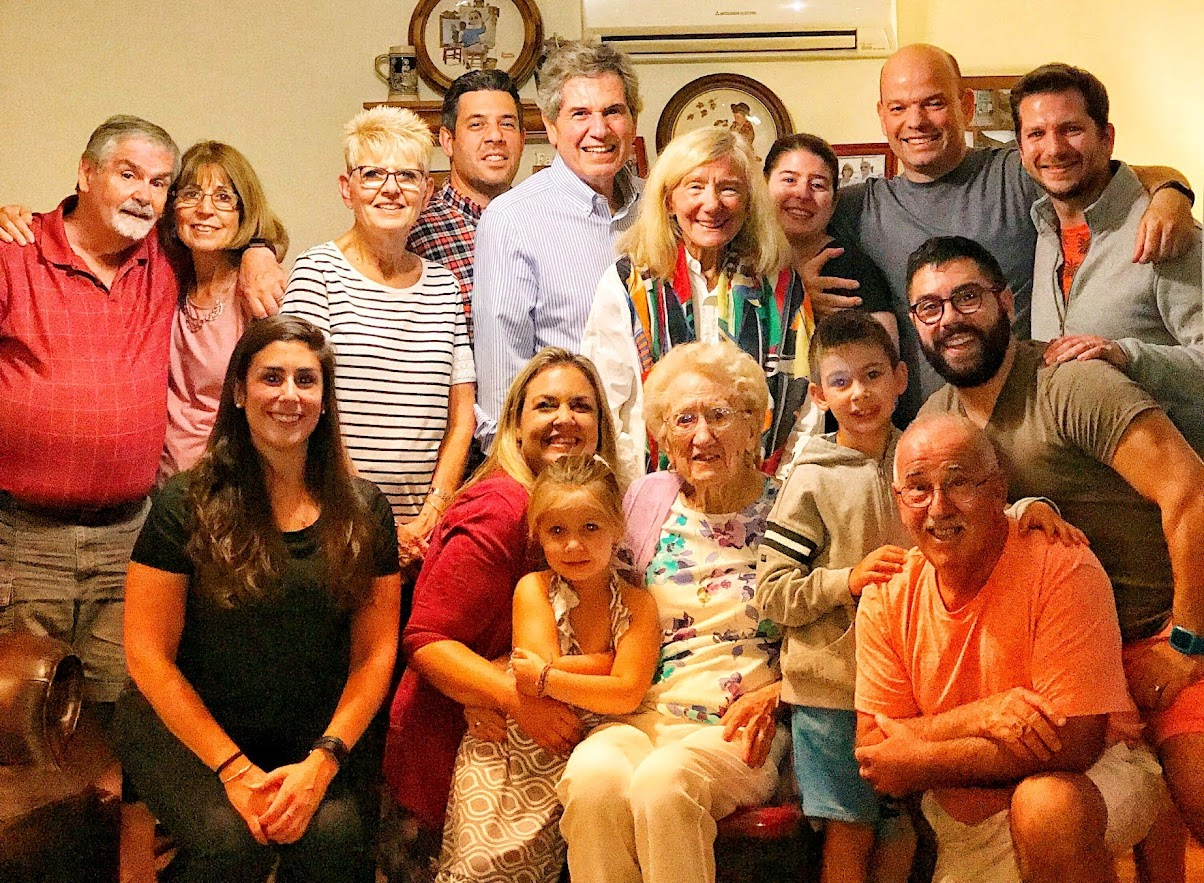

At his funeral, Carlos' sister, Ana (pictured above), delivered a wonderful eulogy in which she told the whole story.

Ana said that Carlos' one wish before he died was to be able to take a shower in his very own, brandy new shower. With tears in her eyes and her voice choking up, Ana said, "Two weeks before he died, he got to take that shower in his new refurbished bathroom."

Erin and I have been together for almost twenty years. I was very close with her grandmother. When my mother died in March of 2021, I grew even more attached to her grandmother. I needed that maternal figure in my life.

Erin and I would visit her grandmother every Saturday afternoon. We'd play bingo with her for a bit. She LOVED bingo.

She was fascinated when I told her we didn't need to use her old bingo set with the spinning cage that housed the balls with the numbers on them.

I told her we could use an app on my phone that is specifically designed to call out bingo numbers. She was fascinated, which is not to say she preferred it over the old-fashioned way. Every once in a while I'd catch her leaning in to hear the phone call out the next number, and I'd see her give a random chuckle and shake her head in disbelief.

After bingo, she would insist on making coffee. She'd open a box of Sara Lee and we'd have a slice of cake with it.

Her coffee would always have a couple of coffee grounds floating around the top, but Erin or I would never dare say anything.

If were still there at 7 o'clock, we had two choices – either we could leave or we would have to move to the living room to watch Wheel of Fortune.

God bless her grandmother, she lived to be 101 years old and she was as sharp as a tack right to the very end – reading as many as five or six books per month.

We couldn't keep up with her. On our weekly visits, we'd bring her two or three romance novels we'd purchased for a dollar each at our local library's weekly sale. When we'd see her next the following week, more often than not, she'd ask if we had brought any more books because she already finished the other ones.

Despite being one month short of her 102nd birthday, the end came as an unfortunate surprise to us. It was August of 2021 – only five months after my mother passed.

Her life wound up being bookended by the Spanish Flu pandemic of the late 1910's and COVID in 2021. It is amazing to think of it like that. The things she must have seen and been through.

She didn't die of COVID, however, but, instead, similar to the Pope, she caught a double pneumonia which hospitalized her. She was in and out of consciousness the first few days she was in the hospital. The situation was pretty bad.

Every time, however, we thought we were losing her, she'd bounce back. I know she had been given the last rites once, if not twice.

Erin and I would visit as much as we could, but COVID limited hospital visitations to only a couple hours per day and only two people at a time.

Then, around the end of the first week in August, the doctors told the family, once again, that they thought the end was near. I knew the other couple of times the doctors had given us this prognosis that it wasn't her time yet. Erin's grandmother was the toughest woman I've ever known. She was a fighter.

I remember Erin's mother telling me after the first time her mother recovered, despite being given last rites, "You were right, Tony. Even I didn't think she was going to bounce back."

But something felt different this time. Erin and I visited her grandmother on a Friday. This time she looked too frail, too weak. When I held her hand, I didn't feel any sense of fight left in her like I did the other times.

I took advantage of having a little extra time with her because most of her kids and grandkids and great-grandkids en route from different parts of the country. I put my phone close to her ear and played her favorite singer, Dean Martin ("now that is one good looking man," she would always say).

She didn't respond to anything. She didn't open her eyes. She didn't try to talk. I told her her grandkids would be here on Sunday. I told her she needed to hang on a couple more days.

Not only did she hang on, two days later when her whole family visited her at the hospital, she was sitting up in her bed and talking to her family members like it was just one of those normal Saturday afternoons when Erin and I would come by her house to have coffee.

Two by two, I'd be sitting outside and hearing the stories from the family members as they left. The visiting restrictions of only allowing two visitors at a time was still in place, but they extended us the courtesy of extending visiting hours for her to accommodate everyone that was coming.

I chose not to go up that Sunday in order to give everyone else a chance. I had already said what I needed to say to her – basically, promising her that she needn't worry about Erin, that I would take the best care of her.

It was, absolutely, amazing to see everyone smiling, and with a look of amazement on their faces, as they walked out of the hospital doors that day. They'd stop to see me sitting on a bench and they'd all tell me a variation of the same thing,

"She doesn't look like someone who is dying. People were telling us she was unconscious and not talking or eating or responding to things. We were worried we wouldn't make it here in time. She's up there having full conversations with everyone. She looks great!"

Erin's sister is a sports journalist who covers the Red Sox. When she came outside after visiting her grandmother, she was telling Erin and I that grandma was asking her questions about how the Red Sox are doing.

Another grandson of hers owns a comedy club and when he came outside he told us that she was asking him about what comedians he has booked for the coming months.

Even when Erin's mother came out, she was absolutely amazed. I last went up to the room to visit on that Friday when I told grandma she needed to hang on until Sunday for when the family was all coming in.

Erin's mother told us that the following day, Saturday, grandma was the same as Friday – unconscious and not responding to anything.

Then, on Sunday, Erin's mother arrived first to find grandma sitting up all alert and talkative. It was an absolute miracle that for that one final day, the nearly 102-year-old wonderful, beautiful woman pulled it all together to allow her family to remember her the way she had always been – vibrant, funny, inquisitive, and caring.

The following day, she slipped into unconsciousness again. Two days later, she had gone to heaven.

My mother passed away five months prior to Erin's grandmother. That would have put is even earlier into the COVID pandemic.

It was March of 2020 when our country admitted the magnitude of the disease and put the country on lockdown. My mother had already been in nursing homes for a few years, at this point. By this time, her Lewy Body Dementia had progressed to a point where she didn't recognize me when she saw me.

Beginning in March of 2020, however, it didn't matter if she recognized me or not because she wouldn't see me, hardly at all, for the next twelve months. Visitations were banned altogether. No one was allowed to visit.

My mother died on March 31, 2021. I remember it was about two weeks after that in which the government, significantly, loosened visitation restrictions on nursing homes. Family members were rejoicing they could now visit their loved ones more frequently. I remember thinking to myself, "Just great!"

I only got to visit my mother three times in the final year of her life. It eats away at me to this day that I feel she may have thought we (but, especially, I) abandoned her.

I know, logically speaking, she was in the late stages of her dementia, therefore, she didn't know if I hadn't been there in a year or if I was going there every day. But, I don't care about logic or science or medicine. In my heart of hearts, as a son, I feel she knew I wasn't there for her in her final year.

But, I digress. Getting back to the point of the article and moments of lucidity.

So I only got to visit her three times after March, 2020. I think the first time may have been six or seven months later – in about September or October when they, finally, lifted the complete bans on visitations.

Nursing homes were being hit hard with the spread of the disease, if you remember. Once one person got it, it spread like wildfire through the nursing homes.

When I saw my mother that first time, the visitation had to be outdoors. They had a tent set up for visitations. We were only allowed fifteen minutes and touching was prohibited, but I didn't care. I hadn't seen my mother in months, so I was going to hold her hand and kiss her cheek as much as I could sneak in.

I was so excited when they wheeled her out of the building on her stretcher. My excitement changed to sadness, quickly, when I saw that she was all bundled up and very frail. It looked like she had lost twenty pounds. The nurses had given me updates on her weight whenever they called, but now that I saw my mother, I was shocked. This is what 94 pounds looks like?

She mostly kept her eyes closed, but would, occasionally, open them to look around to take in her surroundings. She was always nosey and did love to gossip. I could see her checking out other families visiting with their loved ones and sometimes she would make faces. I could, absolutely, tell what she was thinking when she made those faces. I knew her better than anyone.

Unfortunately, when she did look at me, it was a look of emptiness. It killed me, especially after all these months of not seeing her, that I couldn't sense for one second that she was looking at her son – her son that loved her so much and that she had loved so much.

Wintertime came and, since they hadn't lifted bans on indoor visitations, I didn't get to see my mother again for several months. It was too cold outside.

As winter drew to an end, I kept checking the forecast to find a warm enough day that would provide me with an opportunity to visit my mom. When I saw an opportunity, I called Tascha.

Tascha was a wonderful nurse at the nursing home for whom I will be, eternally, grateful for being so caring and sensitive to my situation (and who sometimes bent some rules for me).

Even though they weren't really supposed to do outside visitations yet, she arranged for me to be able to see my mother for a few minutes that first week of March.

She warned me, however, to prepare myself for what I would see. My mother was down to 79 pounds and, most days, she wouldn't open her eyes or communicate with anyone.

Nothing could have prepared me for what I saw that day. When Tascha wheeled out my mother, I immediately started crying. This couldn't be my mother. I wasn't looking at a human being. I was looking at a bag of skin and bones. My mother's cheeks were sucked in. Her jaw protruded like an evil witch. Her mouth was gaped open. Her hair was stringy and thinned out. Her skin wasn't a natural color. It was ashen.

I was devastated. She already looked dead.

I didn't bring my dad to visit that day. Because Tascha had warned me, I wanted to see how bad my mother's condition was first, before bringing my father.

But now I knew I had to bring my father to see her, and I had to do it soon. I mean, she was down to 79 pounds. She wasn't eating. How much more could she lose?

The end was near, I was afraid.

I felt better that I had seen my mother first so I could better prepare my father. It would help the situation if we weren't both in shock when we first saw her.

I texted Tascha and set up a visitation for the following week. She responded with a bit of good news. She told me that when we come to visit, we could meet inside because the state had lifted some of the restrictions on visitations indoors.

Woohoo.

I really wasn't excited. That was 100% sarcasm. Too little, too late in my eyes.

As I drove to the nursing home with my dad on the day of our arranged visit, I was in dread. I had done everything I could to warn my dad. He didn't believe it could be as bad as I was making it out to be.

When I pulled into the parking lot, I texted Tascha to say we were there and awaited instructions on where to go.

She responded with a happy face emoji.

I found that odd. Was she happy I was there? What did that mean? I had grown friendly with her over the past year, but I found the happy face emoji to be a bit inappropriate and unprofessional for the circumstances.

Her next text was something to the effect that she thinks I am going to be happy when I see my mother. She then tells me to come in and go to the 3rd floor and all the way down the hall and to the right where the dining area is.

Interesting. My dad and I put on our masks and we go in through the entrance and take the elevator to the third floor. My mind is racing as we walk down the hallway to the dining area. Can't my dad walk faster? Jeez.

I can't get to the end of the long hall fast enough, but I have to keep slowing down so my 86-year-old dad can keep up.

Tascha meets me at the door with a big smile.

"She's over there," she says as she points over to a corner. I see a wheelchair turned away from us, facing the wall. Sticking out the sides of the wheelchair, I can make out some tiny hands fidgeting, restlessly, with the armrests. I can see a head bobbing to the side as if the person is looking for something.

"That's her?" I ask, in utter disbelief. Where is the stretcher?, I think to myself.

"Yeah, that's her. Go on over," she says as she almost pushes me to get moving.

The thirty minutes that followed will be thirty minutes I will treasure forever. My mother was sitting in the wheelchair, eyes wide open, and mumbling words. She didn't recognize me, I don't think, but I felt confident she recognized my father.

Some doctor, therapist, or nurse somewhere along the way had told me that the last person a dementia patient forgets is his/her spouse. That was of little comfort to me. I wanted my mother to never forget me, but if she did, I wanted to be the last person she forgets.

But I had noticed, for a while now, that she would, almost always, show signs of remembering my dad, even in these late stages of her dementia.

The last few weeks my mother stayed at home with us, she would constantly wander around calling out my dad's name. It drove him nuts. He couldn't leave her side for a second without her calling out for him. I think it may have been a big reason why he, finally, decided to find her a nursing home.

Even in the nursing homes, sometimes I would ask the nurses, or even Tascha at this last home, if my mom ever asks for me. The answer was always, "No, but she asks for your dad a lot." Grrrr.

But, on this day, I was able to put any resentment towards my dad aside. This was as much his moment as it was mine. Who am I kidding? This was more his moment. They had been married sixty years.

I had to admit it was cute watching my mom and dad interact. I'm so glad he got to see her like this, and not like the way I had seen her the last two times I visited without him.

Just a week ago, she looked like death. I was worried every day since then that I would get the dreaded phone call. I wouldn't have been able to live with myself if I had seen my mother that last time by myself, and if my dad never had gotten a chance to say a final goodbye because I didn't take him with me.

Yet here they were, almost playing – like little children – with each other. They'd swat each other's hand away. I think she stuck her tongue out at him one time, and he stuck his out back at her.

The best was when, towards the end of our visit, despite both of them wearing masks, he leaned over to kiss her on her mask, and she tried swatting him away, gently, as if he were a mosquito flying around her face.

I got to take one final picture with her. I got to kiss her goodbye. I got to tell her I love you. I know she heard me. She might not have known who I was or what the words meant, but I got to say them to her. I got to look into her eyes and she looked into mine. This was my mother.

When I was leaving the dining hall, Tascha came over.

"Isn't it incredible? Doesn't she look great? It's amazing. I told her this morning that you and your dad were coming and next time I came into the room, she is awake, mumbling, and stirring around."

"It's an absolute miracle," I responded and thanked her for the millionth time.

This was great, I thought. The worst of the pandemic seemed to be ending. I'd be able to visit my mother more often. She looked like she made a bit of a recovery.

However, I fell trap to terminal lucidity.

I was told years ago that dementia patients die because, at some point, they forget how to even eat, drink, and breathe.

About seven to ten days after that visit with my dad, I got a phone call from Tascha. I could hear the tears in her voice. She fell under the spell of my mother just like countless people before her. She fell in love with my mother.

"She has stopped eating, Tony. She hasn't eaten in three days. There is nothing we can do. I think you better get yourself and your family down here," she said.

Two days later, my mother was gone.