Stutz

The documentary begins with Hill saying he was doing the film to get his psychiatrist’s ideas out there. He ended the documentary by saying he was doing it as, essentially, a labor of love and tribute to his psychiatrist.

Actor Jonah Hill decided to make a years-long documentary about his psychiatrist. The documentary begins with Hill saying he was doing the film to get his psychiatrist’s ideas out there. He ended the documentary by saying he was doing it as, essentially, a labor of love and tribute to his psychiatrist. You will hear the word "love" several times.

The aforementioned psychiatrist is Phil Stutz. My first impressions of Stutz was that this guy was different. This Dr. Phil is not your typical psychiatrist. As Matt Damon said to Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting, “Jesus Christ, you talk more than any fucking shrink I’ve ever seen in my life.” Stutz is not the type of psychiatrist to sit back and just listen as the client goes through a stream of consciousness, interjecting the occasional “And how does that make you feel?” or “Go with that.”

Hill puts it this way in the beginning:

“And I was thinking about how, in traditional therapy, you’re paying this person, and you save all your problems for them, and they just listen… and your friends who are idiots, give you advice unsolicited. And you want your friends just to listen. And you want your therapist to give you advice.”

Stutz is a bit potty-mouthed, but isn’t that the world we live in now? He is real. He also seems to break any unwritten, and written, rules that may exist between psychiatrist and client. He even joked at one point of being intimate with Hill’s mother.

It makes one wonder how he hasn’t been disbarred in all these years. He crosses that doctor-patient line throughout the documentary with Hill. Granted it was a documentary about him, but one can imagine the relationship Stutz and Hill have off camera. There is definitely a father-son vibe going on. At one point, Stutz is dribbling a basketball and posting up Hill while on set in between scenes.

Stutz worked as a prison psychiatrist early in his career before making the move to LA, earning a reputation as the shrink to the celebrities. In a way, he went from one prison to another. His experience dealing with prisoners probably helped him deal with celebrities in Los Angeles. Los Angeles is their prison. The media and paparazzi are what keeps these celebrities in their prison. Think Prince Harry and Meghan Markle.

So that brings us to Jonah Hill. Hill lost his brother suddenly from a pulmonary embolism in 2017 at the young age of 40. Hill refused to talk about the incident at the start of the documentary, saying the documentary was about Stutz, and not him. Hill relented midway through the film, focusing on a picture Stutz took of Hill the day his brother died.

Hill also discusses the day-in and day-out scrutiny of his weight, presenting a life size cutout of 14-year-old him when he was horribly obese. Hill gained a reputation of being that “funny, fat guy.” It has worked out profitably for the likes of Chris Farley, Zach Galifianakis, John Goodman, Rebel Wilson, and Melissa McCarthy. While it made these people rich and kept them in high demand, it wasn’t healthy for the individuals on many levels. Do you want to always be known as the "funny, ugly guy" or "the funny, dumb guy"? And then if you are no longer ugly or dumb, then are you no longer funny and are you now unemployed?

You can easily see where Hill could be conflicted. “I had no healthy self esteem,” Hill said. “It intensely fucked me up.” And Hill explains that when he thinks of himself, he still envisions himself as that obese 14-year-old.

Much of Stutz’ philosophy revolves around always moving forward, “putting another pearl on the necklace.” He preaches about refuting the idea of perfection. It is not possible, so don’t feel bad when you inevitably don’t achieve it. In Stutz’ words, there is always a turd. Hill refuted that he sees it as there is a pearl in every turd - meaning there is always some kind of good that can be extracted from every bad situation. Both ideas, taken together, are true, and one needs to acknowledge them in order to move forward.

“The hardest thing for me in life is getting out of bed,” Stutz says at one point, referring to the physical toll Parkinson’s disease has taken on him. The disease is always an undercurrent flowing through the documentary as you see Stutz going through various stages of shaking, slowly searching for his words, and fumbling with his pills.

Hill jokes that he has the same problem getting out of bed, but for different reasons. They share a laugh, but anyone who has battled depression, knows it isn’t all that funny when you are curled up in the fetal position under the blankets not wanting to face the world. It can be just as paralyzing as a serious physical condition.

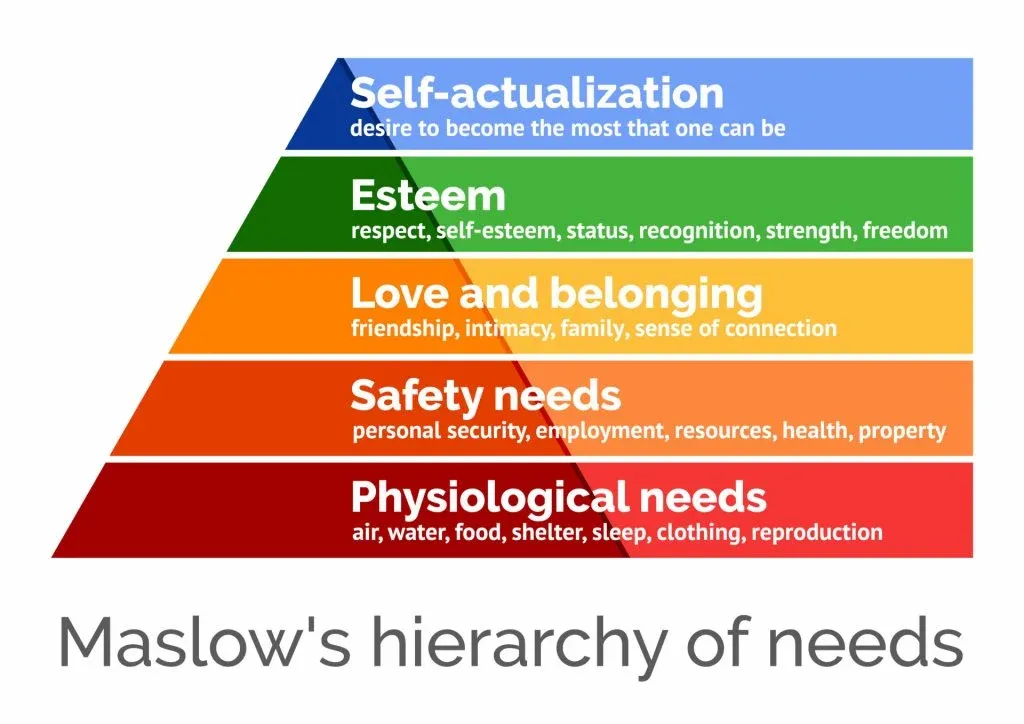

Stutz describes how we need to work on our life force. He draws a pyramid with the bottom level - the foundation - being taking care of your physical health. Exercising, sleeping well, and having a healthy diet are all critical to good mental health.

The second level has to do with relationships. It is important to socialize, but it is more important to have positive relationships and cut out the toxic ones.

The very tip of the pyramid, the cherry on top, is dealing with yourself. How do you view yourself? What are your goals? What are your values? Take time for yourself - meditate, go for a hike, journal, find a new hobby.

The whole idea is reminiscent of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

What stuck out to me though is Stutz speculating that 85% of our mental health depends on our physical health. The older I get, the more I understand the correlation between physical and mental health. Somebody like Stutz can be forgiven for slipping into depression, because Parkinson’s has deprived him of his physical health. Unfortunately, he had no control of that. But Stutz is not depressed, he is grateful. At one point, Stutz takes a break to do some push ups on some random camera equipment. He tells Hill as he does it that he does 100 pushups every day and it makes him feel better. There is no debate that one feels better after exercising. It is just having the motivation to do it that is the problem. Shouldn't the knowledge that you will feel better afterwards be motivation enough?

“Because the highest creative expression for a human being is to be able to create something new in the face of adversity.” You think of people with terminal illnesses becoming formidable artists. Heck, even George W. Bush has become a decent artist after getting burnt out being President of the United States for eight years.

You may even think of people suffering from serious depression and/or grief turning to writing amazing blogs (ahem, ahem).

It would be understandable for Stutz to give up on any chance of improving his physical health knowing his prognosis. But he insists on doing pushups every day. But he also knows when he needs to stop, and just take a nap. Which he actually does at one point, halting the filming so he can go lay on a bed on set, and rest.

“A pity party is a waste of time,” Stutz says. “I get in it ('pity party zone') all the time, but I am very fast at getting out of it.” It would be easy for Stutz to feel sorry for himself, but he doesn't dwell on his disease and instead chooses on moving forward with his concepts. He has too many things to accomplish before he dies, he says.

Stutz talks about several other concepts. Besides life force, he discusses his idea of radical acceptance. It was, basically, putting a name on what Hill and Stutz touched on earlier. He mentions squeezing the juice out of a lemon - meaning finding something valuable and meaningful in any bad event. Stutz explains that were it not for his Parkinson’s, he wouldn’t have been able to fine tune his ideas and concepts.

Another tool Stutz touches on – after all, one of the reasons for making this documentary is to promote his ideas – is the idea of The Grateful Flow. He makes Hill go through an exercise where he needs to think of two, three, or four things that he is grateful for – the smaller the thing, the better. Stutz says to do this every day, but never repeat the same things from one day to the next. Dig deeper.

“The key is not saying the same things over and over and over again that you’re grateful for. You wanna make it a creative act. When you have to dig and work on it to find these things, that process itself will change your mood.”

Towards the end, Hill does bring up his brother and Stutz uses this as an opportunity to address his idea of loss processing. I admit I perked up at this point because that is what I am dealing with, having lost my mother a couple of years ago and not being over it to this day.

Stutz says that most people are bad at processing loss. I am guilty as charged. Stutz talks about not getting overly attached to something or someone, because you will lose it at some point. Don’t be afraid to lose it.

While I couldn’t relate to that concept too much, I did appreciate his next thought. He said that death is not a permanent condition. He talks about the likelihood of rebirth. Dying is just a part of a process. It is not the end all be all.

Stutz has Hill close his eyes and picture himself hanging from a branch, letting go, feel himself slowly falling, before crash and burning up on the surface of the sun, and turning into a sun ray among many others.

I don’t know how I feel about the crash and burning up part, but I appreciate the thought that our body is vastly overrated, and we should detach ourselves from the idea that our physical bodies are who we are. Essentially, we are energy, or sun rays as Stutz would put it.

I guess I am comforted in some ways by thinking of my mother as a warm sun ray touching my cheeks.